We’re not even in the race

I guess I say this a lot in these emails, but I’ve never had a day like Saturday in my life. The drop out rate in Kenya is almost 70%, but when lunch is provided, the numbers tend to drop dramatically. We hoped to decrease the drop out rate and help children learn a little easier.

The plan was that all the maize and beans would be delivered to the orphanage where they had a guarded locked room. On Saturday morning at 8, I would bring some strong young backs and we would load them in a truck we rented, and deliver it to two schools.

By 9 the truck was there, and the 23 bags of beans had been delivered. But the pastor, who knew how to get to the schools, was nowhere to be found and the maize had not arrived. I really didn’t know what to do, and so I went in the car and tried to find a woman that had bid on the maize. While I was looking, the pastor called me on the cell phone and told me he was ready to go.

I headed back, and the maize showed up in a large truck. (75 bags of maize, each bag weighing about 200 pounds, take up LOTS of space) I had paid the guy half the money, but he had not delivered it on Friday when he promised, and I didn’t have the money with me.

Me: I will pay you on Monday.

Him: Pay me now, or I leave.

Me: Then leave half the maize; I’ve already paid for that.

Him: Just go get the money.

At this point, I knew it would take me an hour to go get the money. Fred was with me, so I told the guy `I will give Fred a note and you can go with him to my house and my wife will pay you.’ He agreed, so we transferred the maize and finally left to go deliver the food.

Except we were on Kenyan time. After a good ninety seconds of driving, the pastor told me to pull over, because he needed to buy some food for a conference, so we waited twenty minutes while he purchased food.

It was easy to catch up with the truck. They had been pulled over by the police because it was in poor condition. I got out of the car and explained the situation to the police, and they said we could go.

I have never driven a four-wheel drive vehicle before. Basically, I was a pretty boring guy before I came to Africa. But we pulled off the main road, and quite soon I realized that I was driving like I had never driven before. I went through two streams, was backed up by a donkey cart, and saw several zebra and gazelle running near the school.

The first school we went to was Nyakinyua. It is a school of about 350 children in a poor, poor area. Right behind the school, ten miles away or so, is the telecom dish that serves all of Kenya. How odd must it be to be so poor, and see such great wealth so close to you. We were able to deliver all the food. The headmaster was so grateful, and large numbers of children kept coming up to me and asking: `Is it food for us to eat?’ When I would tell them yes, they would jump up and down.

At this point, I started to know the difference between a 20-year-old Kenyan and a 47-year-old white guy. It took me and two other smaller guys to lift one bag. Everyone else was putting it on their backs. It would have broken mine in two.

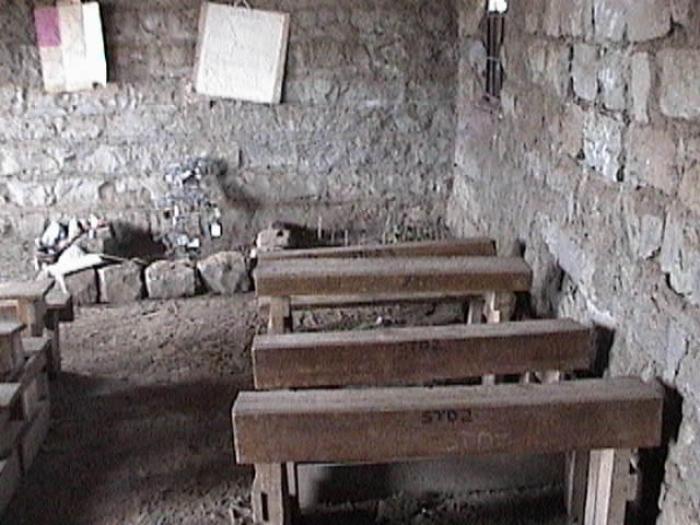

The pastor told me there was a third school he wanted to add, and since we were near the school, he asked me to drive by it. But once we were within a mile of the school, there was no road or anything close to a road to get to it. The school was all wood, with dirt floors, and no windows. It was the poorest school I’ve seen. It is called Namuncha School, and it is attended primarily by Masai children, who live in mud and dung huts. They only have about 150 students, so we had enough to provide them food too.

The other schools are made of brick. Namuncha was made of wood, with no windows and dirt floors. It was almost impossible to believe that children would spend large parts of their days in a place like that.

We then passed by the pastor’s church, and unloaded the food he had purchased. I was invited to eat lunch with them, which consisted of cabbage, beans and cooked carrots. It was good food and fun conversation, although three different times I would yell `It’s time for an English break!’ and they would have to speak in English for five minutes.

After our lunch, we started towards the third school. Have you ever been in fog so thick you couldn’t see in front of you? That was how I was but it wasn’t fog.

It was dust.

After a few minutes, the pastor said to me in his quiet voice: `If you go further, we will not live.’ And darn if there wasn’t about a 30-foot drop off right in front of me. I slowed down.

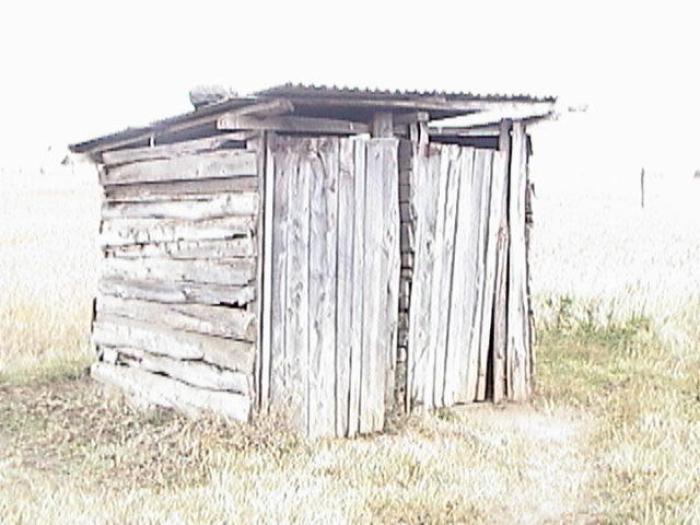

We got to the last school, Kamuyu, and delivered the food. What struck me more than anything is where the children go to the bathroom. I hope the picture captures the sanitary conditions for 250 children with no water.

We started back home, and I noticed that I was sore in the same way you might be after riding a horse for the first time. I was sore in ways I had never been before. It was almost like I had a blister where the moon don’t shine, and I’m sure it was from going up and down all day long on the rough roads. There are bad aches and good aches; this was a good one.

About 800 children, most of whom don’t eat breakfast or lunch, will have a hot, nutritious lunch for the next three months, thanks to all of you. I’m so grateful for what you did.

There is a big conference in South Africa next week, and one of the issues is development in the third world. Colin Powell, a man I respect as much as I respect anyone in the world, was quoted as saying that `We are in a marathon, not a sprint.’

I understand what he means. But when I read the quote, all I could think of was, if they were his children or my children, we would run like we were on fire.

When children have to live like this, and we know about it and let it continue, we’re not even in the race.

Your pal

Steve Peifer

The textbooks the children use at Nyakinyua

The inside of the Namuncha School

Washroom facilities for 250 students at Kamuyu.