A trip north

The cost of drought

Drought has its winners and losers.

The winners are few but easy to spot: hawks and vultures cutting circles in a white-hot sky while scavenging dogs pick through the rocks below.

Then there’s everyone else. A somber, silent mass of livestock, wildlife, and people move through their daily routines, bones growing sharper, tissue collapsing in slow motion.

In the past three years, northern Kenya has weathered five failed seasons of rain. When I think about drought, I assume thirst is the biggest threat, but groundwater fracture zones branch beneath the soil, allowing communities to pull water to the surface through boreholes and hand-dug wells.

Instead, it’s hunger that proves lethal — the lack of grasses and leafy bushes cause animals and then people to fade.

Heading north

In 2020, we first began an emergency lunch program in northern Kenya at the prompting of friends who live there. We’d intended to visit that year, but the pandemic complicated those plans. This year we finally made the trek northward.

From a mile above the ground, we were stunned by the arid, fissured landscapes skimming beneath our tiny Cessna. The bleak plains and slopes looked so little like the Kenya we know.

Kalacha, Kenya

Our first stop was Kalacha, where our lunch program feeds more than a thousand students in two schools. The air around us was hot and restless, stirred by a near-constant wind that churned the dust into a fine sheen of copper.

With limited time on the ground, we decided to divide and conquer: Mark and Lucy headed to Kalacha Primary while Sheri and I spent the morning at Kalacha Nomadic Girls School. The headteacher at the girls school was a bright, incisive woman lit with the kind of fire that ensures her students are educated and cared for.

The one good thing about the drought, she said, is how competing obligations evaporate. With no sheep or goats to tend, children who usually look after family livestock now have excellent school attendance. And in schools with lunch programs, students happily show up for the food.

Meanwhile, at Kalacha Primary, Mark and Lucy stepped into the storeroom and found fewer bags of maize and beans than expected. It turns out that the school had given food to the early childhood students in the area.

“We have food and they ask,” the head teacher explained. “What am I supposed to say to them?” It strikes us afresh that no matter how little our schools have, they readily share with others in need.

Rage Primary School

With the sun cresting into early afternoon, we drove out to Rage (rah-gay) Primary, a small school that hoped to join our lunch program.

Rage comprises a smattering of stone buildings surrounded by a sea of sand and scrub. We surveyed the salt-bleached desert rolling out in every direction and wondered: Where are the houses? Where do all these students come from?

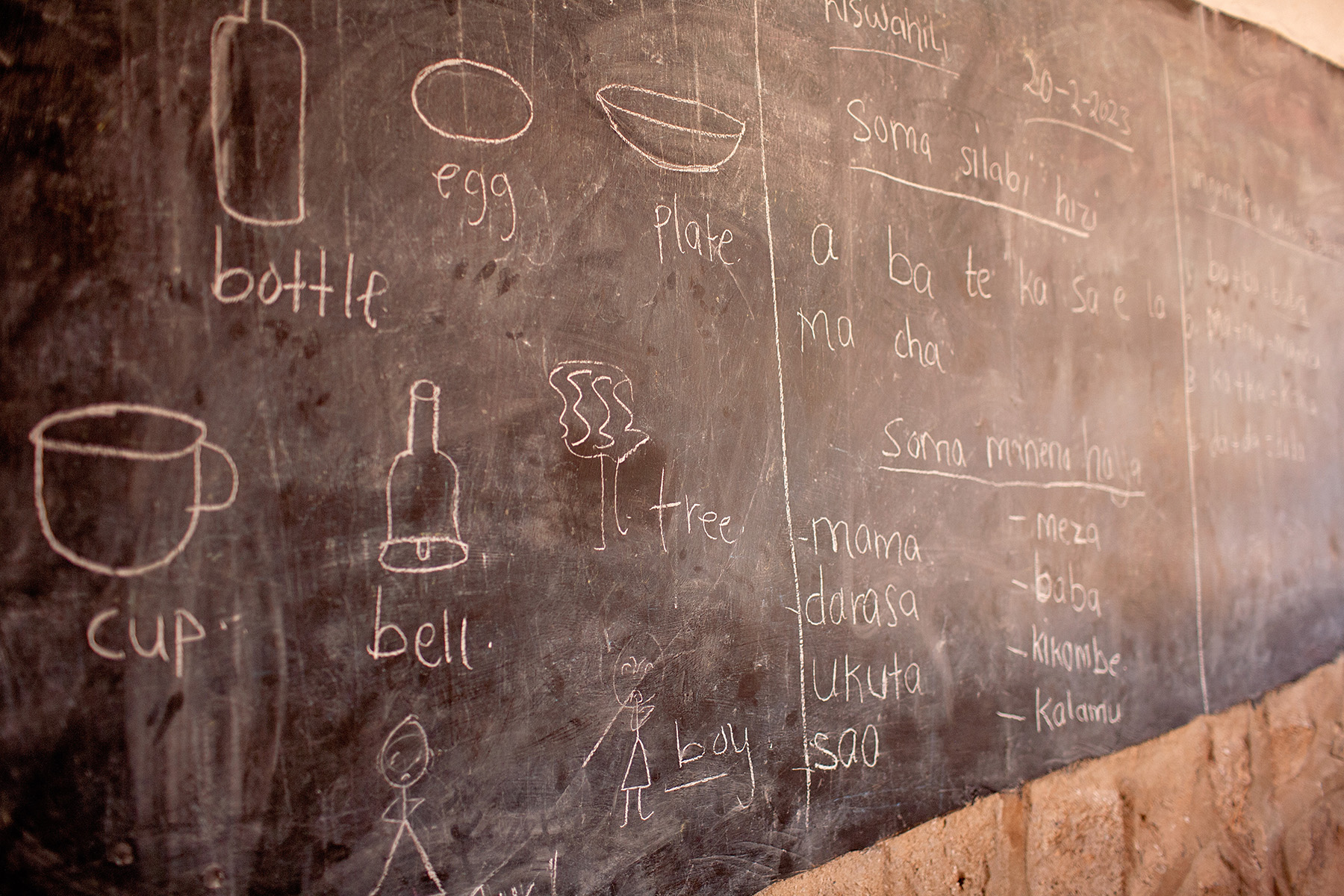

In the spangled shade of acacia trees, children formed letters from rocks or silently observed their teacher weaving a hand broom from bundled reeds. It was impossible to know if their stillness came from being absorbed in their work or from a lack of energy.

Several lifetimes ago I was a teacher of small people in the States, in a classroom of trapezoidal tables and bright posters. Our weeks smelled like crayons, floor wax, spaghetti, and canned pineapple. I knew school looked different in other countries, but I couldn’t have begun to picture this: how teaching in leaner parts of the world is underlaid with an urgency to feed your students.

Dukana, Kenya

We traveled to the town of Dukana next, visiting two more schools that had heard rumors of lunches in Kalacha. At the boys school, the headteacher’s appeal was the same as Rage’s: You are here. You see our need. Please bring the lunch program to our students too.

The government supplies food when it can; to make it last a little longer, teachers at the boys school send kids home for lunch if they live nearby or have a relative who resides in town. What we didn’t discuss is that even though students are sent home for lunch, this doesn’t mean there’s food at home to eat.

Dukana Nomadic Girls School

The headteacher at the girls school seemed weary but resolute as we met in the damp heat of her office. She explained, her voice matter-of-fact, how she makes the rounds each week petitioning the county, churches, and local aid groups for donations, trying to scrape together whatever she can find for her students.

This teacher’s ties to her school are more personal than most: Having attended as a student, she later requested to return here to teach.

When we asked if the school has food today, she said yes, she had bought food that morning. At the storeroom, it took a few seconds for our vision to adjust to the dim interior. Sure enough, two sacks lay empty on the floor while a third held a couple of pounds of rice.

Tragedies ought to be jarring, conspicuous, garish. They should grab our attention and refuse to let go. But hunger is quiet and slow, measured only by absences. Height not gained. Muscle unformed. It’s as silent as loose dresses and shirts draped on tiny frames.

Walking back across the schoolyard, Sheri said what I suspect we were all thinking: This is an entirely different level of hunger. And these head teachers are more akin to development directors. They’re intent on educating their students, of course, but their most vital task is keeping struggling families afloat.

As we walked, the students flocked to Lucy, taken with her elegance and poise.

The trip back home to central Kenya was contemplative and sober.

“You see things on TV,” Lucy said, “but you don’t know that they’re real.”

Before driving the final 90 minutes to our houses, we gathered around a table with a question lodged between us. We’d never before encountered such clear need. How should we respond?

A path paved with hope

Typically we raise support for new schools before bringing them into our lunch program, but this time we reversed the order. Two weeks after our visit, as a supply truck traveled to our schools in Kalacha, we more than doubled the delivery to also send food to Rage and Dukana.

We invite you to join us as we feed our new students in Northern Kenya. So far we’ve been relying on one-time gifts and pulling from our reserves to provide lunch to the 1,450 students at Rage, Dukana Primary, and Dukana Nomadic Girls School. We’d love to bring them into our program long-term.

If you’re a current fan and donor of Kenya Kids Can, would you consider increasing your giving? An additional $25 each month will provide a filling githeri lunch to 12 children. And if you’ve never before had the chance to give, we’d love to have you join us.

Thank you for your sweet and faithful care for our students. We are so grateful.

Let Us Know What You Think